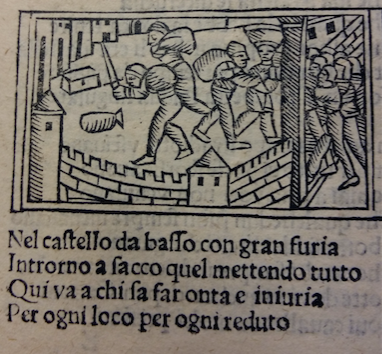

In Niccolò Machiavelli’s late comedy Clizia the unseen Clizia is described as the war booty of Bertram the Gascon, snatched at the age of five and brought back to Florence from Naples in the course of Charles VIII’s invasion of Italy during 1494-5. Machiavelli did not concoct an implausible scenario for his audience – according to every chronicler the rape, ransom, capture, and killing of girls and women by soldiers were regular occurrences during the Italian Wars.[1] It is true that the assembly of canon and civil laws that constituted ‘just war’ theory during the Middle Ages, supported by some Christian and chivalric notions, specified that certain groups (including women) were to be left unharmed during war. In practice, though, the ‘inhumane’ or ‘cruel’ acts (as some theorists put it) of soldiers against women and the unarmed did not vitiate the conflict so long as it rested on a just cause.[2]

There are signs that the horrors of the Hundred Years’ War and the Italian Wars began to shift the balance of attention from causes to conduct around 1500. For example, Philippe Contamine has argued that the concept of bonne guerre, by which non-combatants were spared and those who surrendered were not executed, was spreading from the second half of the fifteenth century and was implemented during the wars of the sixteenth century, including the Italian Wars.[3] The military manuals of the sixteenth century regularly emphasize the discipline and humanity towards the unarmed which soldiers should use, and some praise the adoption by captains of the political virtues of clemency and temperance.

Girolamo Garimberto, in his Il Capitano Generale (published in 1557), allowed that severe tactics could help to subdue rebellious territories. He himself witnessed this at Parma in 1551 when in place of an imperial siege in the name of Pope Julius III the territory was opened to the depredations of the city’s neighbouring enemies and eventually looked like ‘a true image of death’. He also described how it was sometimes necessary in siege conditions for the captain to use, or threaten to use cruelty to put terror (terrore) into the besieged. However, for Garimberto this was an excusable necessity provoked by the abuse of the captain’s ‘humanity’ (l’humanità) and vitiating any thought of clemency by interpreting the law ‘humanely’ (humanamente). It stood in sharp contrast to the case of the person who ‘merits the name of cruel, who by nature or by anger passes beyond the limits of legal severity in punishment, not by any necessity but by choice’. In this way, he argued, like the doctors who, when other medicine has failed, cut of a part of the body to prevent the spread of disease so the cruelty used by captains was to be praised for preventing the spread of obstinacy among the larger part of the people.

Garimberto went on to write that it was in fact more divine than human to show humanity and clemency and to spare the lives of others in a sack and avoid the destruction of a city, a nation, or people. Therefore, in conquering a territory the captain must ensure that it is not sacked and dishonoured on the point of victory for a pardon and clemency brought greater glory than vendetta and destruction and would be of greater utility and bring greater fruits. Indeed, those who were pardoned by the captain would always be his creditors unlike the victims of his vendetta. After all, those who witnessed the sack of their property, the rape of their wives, daughters, and sisters were filled with a spirit of fury and disdain, and would die in pursuit of vendetta. Moreover, allowing soldiers to sack a city would corrode the army’s discipline and he recalled the example of Prospero Colonna who protected Bergamo when the imperialists wished to sack it. [4]

Raymond de Fourquevaux, the author of the Instructions sur les faicts de guerre (first published in Paris in 1548 under the more prestigious name of the noble diplomat Guillaume du Bellay) also argued that the captain should avoid cruelty after a victory in battle, or after having taken a town by force:

But what thing is more inhumane than after having piled at the feet the ensigns of the enemy, sacked their camp, having broken up, put to flight, and undone their battles [sc. troops in battle array] in heat, yet to kill in cold blood those who did not die during combat? Or, after a breach has been forced, and killed those who defended it, still to cut up those who have surrendered? And the poor inhabitants, old and young, notwithstanding that they are unarmed and innocent? And, beyond this, to permit women and girls be forced and sometimes killed, the churches plundered and the sacred things stolen and turned to base uses? Truly, it is worse than cruelty.[5]

The commander was therefore supposed to refrain from ordering such acts except during battle when defenders were still in arms, although even they were to have the opportunity to lay down their weapons and be left untouched.[6]

Many of these concerns about excessive cruelty or inhumanity towards non-combatants are evident in medieval literature, and so I am wary of constructing a narrative of changing attitudes towards non-combatants during the Italian Wars akin to the civilizing process outlined by Norbert Elias (and criticized by a number of historians).[7] Like the attempt to apply the concept of ‘total war’ to the early modern period the sketching of such a narrative immediately raises questions about the definition of ‘civilian’ and the degree to which the civilian can be distinguished from the soldier in this period.

An analysis of the terms used by ancient and modern authors in English and Latin is a good place to start and can be revealing. The English word ‘civilian’, which I have often used in these posts as a neutral term, originally derived from the Old French adjective civilien (pertaining to a student or practitioner of Civil Law) and was a nineteenth-century creation with no pejorative meaning except when used oppositively such as when it was suggested in 1864 that ‘military men view any civilian interference with dislike’.[8] The term ‘non-combatant’ referring to a civilian in time of war, or to a member of the army or navy who did not fight (such as a surgeon or chaplain) originated around the same time, and again did not generally have a pejorative meaning.

By contrast, the Latin term imbellis could refer to those simply unsuited to warfare, including women and children,[9] to those not trained or ready for war,[10] but also to unwarlike animals such as the dove,[11] and frequently in a derogatory sense to those people not disposed to war or fighting, cowardly.[12] In this last case, one of the best-known examples is found in Horace’s Odes (III.2): ‘Tis sweet and glorious to die for the fatherland [dulce et decorum est pro patria mori]. Yet Death o’ertakes not less the runaway, nor spares the limbs and coward [imbellis] backs of faint-hearted youths’.[13] This negative sense was sometimes intended by Renaissance writers including Paolo Giovio who recounted pithily (in c. 1515) that once the French bombardment and assault of Gaeta (near Naples) began in 1495 ‘in every place the populace, bold in words but cowardly [imbellis] in deeds, and assaulted by sudden fear were cut to pieces cruelly’, and therefore some decided to open the gates and throw their arms on the ground before the French.[14] The historian Francesco Carpesani also applied it in this negative sense to the comments made by the French in 1503 about the unwarlike and cowardly nature of the Spanish and Italian troops.[15]

However, the Latin term which perhaps comes close to that of the modern sense of ‘civilian’ as an antonym of ‘soldier’ is ‘paganus’. For example, in a letter to the Emperor Trajan Pliny mentioned ‘milites et pagani’ as two groups that benefited from the humanity and justice of a particular unnamed soldier.[16] The Roman historian Tacitus described how restless and mutinous soldiers in winter quarters with the tribes of Treviri and Lingones, who had been punished harshly by Galba, were ‘demoralized by mixing with these civilian inhabitants [paganos]’.[17] In the fourth century Vegetius seemed to oppose ‘miles’ and ‘paganus’ in a similar fashion, noting in an aphorism popular with medieval and Renaissance readers of his popular text on military matters that ‘in battle, skill is of more benefit than strength; for, if skill in the use of arms is absent, a peasant [paganus] differs not at all from a soldier.’[18]

Even this term lacks the generally neutral sense of English ‘civilian’ or ‘non-combatant’, or even ‘inermis’ (unarmed), which Renaissance writers sometime employed. Tacitus had Antonius address his praetorians before a battle: ‘As for you, clowns [pagani] that you are, if you do not win today, what other general or other camp will take you in?’[19] The term was also applied derogatively in 1124 to the stipendiary knights of King Henry I’s household, who were described as ‘pagenses et gregarii’ (‘country bumpkins and mercenaries’).[20] The Neapolitan chronicler Giuliano Passero may have used the word in a more neutral way when he described how in November 1495 King Ferrante took Nocera from the ‘pagani’ by battle, and it was immediately put to ‘blood and fire’ with prisoners taken and goods sacked. The king issued an edict prohibiting violence against women and ordered that all should be honourably treated like sisters.[21]

Linguistic study can therefore offer some useful hints of the pejorative value which attached to non-combatants during the Italian Wars, and has been noted in Renaissance military memoirs. Further study of the writings of sixteenth-century just war theorists and the manuals of combat advice, for example, may also reveal how the web of meaning might have stretched to encompass as non-combatants those who would not fall into my modern category of civilian, and vice versa. This may reflect the fact that the meaning of civilian was highly contingent on circumstances, and that armies, companies, and soldiers were raised seasonally and did not constitute a permanent force in society. With the appearance of permanent armies and the specialization of functions during the sixteenth century it may be argued that society was more clearly demilitarised. This sharper demarcation of functions may have led to the emergence of a clearer and more stable categorization of civilian, one to be sharply distinguished from that of soldier who would no longer be considered, following Vegetius, merely a peasant trained up in arms.

Finally, research may also show whether concerns about ‘inhumanity’ (as Raymonde de Fourquevaux put it) towards the unarmed increased. Did the consideration of conduct in warfare over the cause of war grow? Returning to Garimberto the answer this question seems to be yes. As he wrote, not all methods (modi) of winning are honourable and a victory can be glorious or inglorious depending on the method used, or according to whether the war is just or unjust. The honourable and glorious means of winning is to shed as little blood as possible, while the inglorious and dishonourable victory involves much bloodshed. There is no doubt about victories in a just war, which being necessary to it are just and consequently praiseworthy; while those in an unjust war are unjust and infamous (infame). But just as some unjust wars have had as an end a victory acquired with prudence, and consequently worthy of praise, so the victories of some just and praiseworthy wars have been lacking in glory. He goes on to suggest that some bloody victories (vittoria insanguinata) are necessary, if not praiseworthy, such as when those defeated in battle and preserved by the captain’s clemency break faith and he is forced to become cruel. However, causing bloodshed simply for the love of bloodshed is to be condemned and there is greater glory, and a greater reputation to be gained by the captain, in pardoning and saving lives. Therefore, acting in the place of reason the captain must restrain the appetites of his soldiers (Bk 3, Ch. 8).

Bibliography

Primary

All classical texts are cited using editions published in the Loeb Classical Library.

Carpesani, Francesco. Commentaria Suorum Temporum (1476-1527). Ed. Giacomo Zarotti. Parma: La nazionale, 1975

Garimberto, Girolamo. Il Capitano Generale. Venice: Giordano Ziletti, 1557

Giovio, Paolo. Dell’Istorie del suo Tempo. Trans. Lodovico Domenichi. 2 vols. Venice: Giovan Maria Bonelli, 1560

— Historiarum sui Temporis. Ed. Dante Visconti. 2 vols. In Paolo Giovio, Opera. Vols. 3-4. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1957

Passero, Giuliano. Storie in forma di Giornali. Ed. Vincenzo Maria Altobelli. Naples: Vincenzo Orsino, 1785

Raymond de Forquevaux [Published under pseud. Guillaume du Bellay]. Instructions sur le faict de la Guerre. Paris: Michel Vascosan, 1548

Secondary

Allmand, Christopher. The De Re Militari of Vegetius: The Reception, Transmission and Legacy of a Roman Text in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011

Cohn Jr., Samuel K. ‘Repression of Popular Revolt in Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Italy’. In The Culture of Violence in Renaissance Italy: Proceedings of the International Conference; Georgetown University at Villa Le Balze, 3-4 May, 2010, ed. Samuel Kline Cohn Jr. and Fabrizio Ricciardelli, 99-120. Florence: Le Lettere, 2012

Contamine, Philippe. ‘The Growth of State Control. Practices of War, 1300-1800: Ransom and Booty.’ In idem (ed.), War and Competition between States, 163-93. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000.

Elias, Norbert. The Civilizing Process, trans. Edmund Jephcott, 2 vols. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1978-81

— The Civilizing Process: Sociogenetic and Psychogenetic Investigations, trans. Edmund Jephcott, ed. Eric Dunning, Johan Goudsblom and Stephen Mennell. Revised edn. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2000

Charters, Erica, Eve Rosenhaft and Hannah Smith (eds), Civilians and War in Europe 1618-1815 (2012)

Johnson, James Turner. Ideology, Reason, and the Limitation of War: Religious and Secular Concepts, 1200-1740. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975

Kaeuper, Richard W. Chivalry and Violence in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999

Lynn, John. Women, Armies, and Warfare in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008

Russell, Frederick H. The Just War in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975

Strickland, Matthew. War and Chivalry: The Conduct and Perception of War in England and Normandy, 1066-1217. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

Wilson, Peter H. ‘German Women and War, 1500-1800’. In Jeremy Black (ed.), Warfare in Europe 1650-1792, 45-78. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005 [First published in War in History, 3 [1996]: 127-60]

[1] For the period after 1618 see Charters, Rosenhaft and Smith, Civilians; Wilson, ‘German Women’.

[2] Johnson, Ideology, Reason; Russell, Just War; Kaeuper, Chivalry; Strickland, War.

[3] Contamine, ‘Growth of State’, 186.

[4] Garimberto, Capitano, 233-4, 285-90, 299-305.

[5] ‘Mais quelle chose est plus inhumaine, qu’apres avoir foullé auz piedz les Enseignes des ennemis, saccagé leur Camp, avoir rompues, mises en fuitte, et detrenchees leurs batailles sur la chaulde, achever encores d’occire a froid sang ceulx qui ne seront mortz durant le combat? Ou apres que l’on aura forcee une breche, et occiz ceulx que se seront mis en defense, detrencher encores ceulx qui se seront renduz? Et les paouvres habitans vielz et ieunes, nonobstant qu’ilz soient desarmez et innocens? Et en oultre, permettre que les femmes et les filles soient forcees, et aucuneffois occises, les temples pillez, et les choses sacrees ravies, et converties en villains usages? Veritablement c’est plus que cruaulté.’ Raymond de Forquevaux, Instructions, fol. 93v [recte, 92v].

[6] Ibid.

[7] On the violence and cruelty of the Middle Ages increasingly restrained by rules and states see Elias, Civilizing Process, 1: 191-217; 2: passim, but especially the synopsis in pt 4. Elias was careful to state that: ‘Our kind of behavior has grown out of that which we call uncivilized. But these concepts grasp the actual change too statically and coarsely. In reality, our terms “civilized” and “uncivilized” do not constitute an antithesis of the kind that exists between “good” and “bad,” but represent stages in a development which, moreover, is still continuing.’ Ibid., 59. He explicitly rejected the idea that medieval manners represented ‘the stage of “barbarism” or primitiveness”’ at ibid., 62, and he questioned the idea of ‘progress’, emphasizing that certain customs must not be viewed as a ‘lack of civilization’ but ‘as something that fitted the needs of these people and that seemed meaningful to them in exactly this form.’ Ibid., 68. He also asserted that: ‘The civilizing process does not follow a straight line.’ Ibid., 186. The preface to the 1968 reprint of his work also clarifies some of his views on the relationship between the ‘civilising process’ and ‘progress’. It was published in English translation in 2000: idem, Civilizing Process, 449-83. On the rise of at least one form of violence – cruel punishment and executions – in Italy after c.1390 see Cohn, ‘Repression’.

[8] However, the OED, which is my source here, records the (presumably short-lived) use of ‘civilianization’ in 1946 as a pejorative term applied to the replacement of members of the armed forces involved in administration by civilians.

[9] Livy, 28.23.2, on the ‘turbam feminarum puerorumque inbellem inermemque cives sui caederent’. Frontinus, Stratagems, 2.4.20 writes of the king of Scythians who ‘iussit a feminis puerisque et omni imbelli turba’ to take part in a ruse. At ibid., 3.9.3 he writes of the castellans of a town recalled from its defense ‘ab imbelli multitudine’ under the mistaken belief that the town had already been captured from the rear, and at ibid., 2.5.19 there is a reference to ‘imbelles’ as the non-combatant part of the population. In Vegetius, Epitoma, 240 (4.7) we find the following recommendation to prevent famine in a besieged town: ‘Inbellis quoque aetas ac sexus propter necessitate victus portis frequenter exclusa est, ne penuria opprimeret armatos a quibus moenia servabantur.’

[10] Livy, 23.46.11, on ‘peditem inbellem’ or ‘infantry unfit for war’; Frontinus, Stratagems, 3.10.1 on ‘Suessetanos quosdam ex auxiliaribus maxime imbelles’.

[11] Horace, Carmina, 4.4.31.

[12] Sallust, Jugurtha, 20.2, contrasting Jugurtha ‘acer, bellicosus’ with his victim Adherbal ‘quietus, inbellis’; Vergil, Georgics, 2.172, on Emperor Augustus driving the ‘imbellum … Indum’ or ‘craven Indian’ (sc. Eastern nations) from the hills of Rome; Livy, 21.16.3, contrasting the Roman impression of the fierce and warlike Carthaginians victorious at Saguntum with a Rome that seemed ‘desidem … atque imbellem’, or ‘torpid and unwarlike’; Livy, 26.2.11, contrasting the warlike Carthaginians with an army of Roman citizens ‘ignavi et inbelles inter hostes essent’; and Quintilian, Institutes, 7.1.43, ‘pro viro forti contra inbellem’, or ‘a war hero against a coward’.

[13] Horace, Carmina, 3.2.15, ‘dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. / mors et fugacem persequitur virum, / nec parcit imbellis iuventae / poplitibus timidove tergo.’ Much more poetic is Jonathan Swift: ‘How blest is he, who for his country dies; / Since Death pursues the Coward as he flies. / The Youth, in vain, would fly from Fate’s Attack, / With trembling Knees, and terror at his Back; / Though Fear should lend him Pinions like the Wind, / Yet swifter Fate will seize him from behind’.

[14] ‘Passim ferox dictis populus, factis autem imbellis, et subito timore consternatus, crudelissime trucidatur’. Giovio, Historiarum, 1: 95.

[15] ‘Nam inter huiusmodi contumeliarum iactationes, audita est vox cuiusdam Galli plus aequo ferocientis et imbelliam ignaviamque Hispanis atque Italis eiusdem commilitii exprobantis. Quam indiginitatis notam minime ferendam rati Itali, misère communi nomine ad Gallos, qui renunciarent, quando imbelles ignavique a se haberentur, eorum praeiudicio cupere secum manu conserta per aequas bellatorum manus utri bello praestarent experiri.’ Carpesani, Commentaria, 87.

[16] Pliny, Epistulae ad Traianum, 10.86b(18).2.

[17] ‘unde seditiosa colloquia et inter paganos corruptior miles’. Tacitus, Historiae, 1.53.

[18] Vegetius, Epitome, 59 (2.23). ‘Postremo sciendum est in pugna usum amplius prodesse quam vires; nam si doctrina cesset armorum nihil paganus distat a milite.’ On medieval and Renaissance readers of Vegetius see Allmand, De Re Militari.

[19] ‘“Vos […] nisi vincitis, pagani, quis alius imperator, quae castra alia excipient?”’ Tacitus, Historiae, 3.24.

[20] Waleran de Meulan quoted by the twelfth-century chronicler Orderic Vitalis and quoted in Strickland, War, 288.

[21] ‘Alli 3 di novembre 1495 lo signore re Ferrante have pigliata Nocera delli pagani per forza de battaglia, e subito fo messa a sangue, e fuoco, e lo signore Re subito fece andare uno bando che a pena della vita non fosse persona nessuna, che facesse violentia alle donne; ma che ognuna fosse honorata come sorella, ma foro ben tutti sacchiati, e l’huomini puosti presuni.’ Passero, Istorie, 88. Passero goes on to describe how the king took the castle of Nocera three weeks later. Therefore, by referring to ‘pagani’ in the aforementioned passage he may have intended to draw a contrast between the inhabitants of the town and the troops in the castle: Passero, Storie, 89.