I have just been in the excellent and helpful Archivio di Stato in Modena for the first time reading eyewitness accounts of the sack of Prato, near Florence, in August 1512 by troops of the Holy League under the command of the Spaniard Ramón de Cardona. I originally read some of these letters, written by the duke of Ferrara’s secretary, the humanist Bonaventura Pistofilo, in a nineteenth-century edition, which omitted some of the more personal details which are of interest to me as I try to reconstruct how Renaissance Italians expressed their reactions to these events of mass murder (five thousand are said to have died at Prato, but the true figure may be a tenth of that).[1]

The trauma of mass murder posed a challenge for those who wished to record or represent such events.[2] As the author of a lament about the sack of Rome in 1527 complained, chronicles and pictures were inadequate to express such dark cruelties.[3] This was a well-worn narrative device to indicate the gravity of the tale to follow. As the author of a lament for the sack of Prato in 1512 put it: ‘In twenty-three hours they made such an assault that the mortal tongue cannot express it.’ Even then, the poet went on, it was hard for the mortal ear to hear about such things.[4] However, witnesses of destruction and mass murder were not always inarticulate with grief or shock, even if the language they used was often less emotionally charged and more communal and providential than its modern counterpart.

Soldier-memoirists, who proliferated during the sixteenth century, were primarily concerned with providing a record of their deeds which would above all confirm their honourable status. Fairly typical of such accounts is that of the Burgundian Fery de Guyon who was with the Spanish army in Italy. His description of the capture of Rome entirely omits any mention of non-combatant fatalities; a tactful silence given his own loyalties.[5] Also apposite is the example of the military entrepreneur and field commander Sebastian Schertlin von Burtenbach, who fought at Pavia (1525) and the sack of Rome, and made enough money to buy a castle. His autobiography (c. 1560-75) was written with an eye on his posthumous reputation and records the ransoms and rewards which he acquired in the course of military career. At the conclusion of his account of the material gains he made during the Italian campaign, which culminated in the sack of Rome in 1527, he declared that ‘thanks to the Almighty, I earned it well.’[6]

This emphasis on ‘services rendered’ and an explicit desire to counter slurs to honour and reputation marked Adam Reissner’s c. 1568 biography of Georg von Frundsberg. Reissner had accompanied Frundberg during the campaign in Italy of 1526-7. He was strongly Protestant and he aimed to counter Italian silence about, or criticism of German knightly deeds in these wars. He argued that the sack of Rome was a form of divine punishment and that the German commanders like Frundsberg had had no choice but to allow the troops to plunder given the failure of payment from Charles V or Clement VII. He had fought to preserve lands and peoples and secure peace, and not for gain.[7]

The way that diplomats focused on the political and military implications of mass murder can also seem callous, but this perspective was formed by the priorities of the profession and the conventions of their forms of communication. In 1494 the Ferrarese ambassador to Florence reported the sack of Fivizzano (and other castles) to his lord with no mention of casualties.[8] In 1512 the Spanish ambassador Girolamo Vich in Rome wrote of the reports he had received, via the Florentines in the French camp, of the massacre at Brescia. He noted the loss of life in the city and described it as a ‘victory with much blood and loss of Frenchmen’. However, the speed with which Gaston de Foix and the French army had retaken the city meant that, together with the French army, he ‘has gained a great reputation’.[9] The reports sent home by the Florentine orators to the viceroy at the time of the sack and massacre in Prato in 1512 generally, and quite naturally, focus on the diplomatic ramifications of the Spanish army’s action, which made the return to Florence of the Medici more certain. For example, at the end of August, while discussing the adherence of Florence to the league and the change of regime, the orators reported that the viceroy asserted that the Catholic king was not in Italy to destroy its territories but ‘to mend them’ (‘rassectarle’).[10]

Our Ferrarese ambassador to Florence, Pistofilo, also maintained a professional calm in his reports to the duke of Ferrara about the sack of Prato and its ramifications for Florentine politics.[11] In a letter to ‘Messer Alexandro mio honoratissimo’, described as a brother of the duke, he wrote: ‘I saw the greatest cruelty that I have ever seen: all of the streets and the very churches were filled with the dead, and I saw little children and women killed.’ He went on to describe how he (and many others) had seen some crows circling and cawing above Prato, although he added that it was ‘superstition to lend credence to auguries’.[12] It was only when writing to a certain Hieronimo, with whom he was clearly on informal terms, that he revealed his feelings in a more emotional key:

For my part I advise you of the capture of Prato, which was taken yesterday by force of battle. These Spaniards made such a massacre and butchery the like of which I have never seen, so that all the streets, houses, and churches themselves were full of the dead, and all of the women have fled to some monasteries and churches where the most miserable laments and pleas that it is possible could be heard. The whole place is put to the sack. I have stayed [here] eight days and neither my stomach nor my spirit is good on account of what I have seen and heard. I would very willingly not stay here. I beg you to send here the [one word illegible] by the posts that come to us. I look for a small bottle of corked Nebbiano [wine], and also a bottle of scordion [medicine] for me.

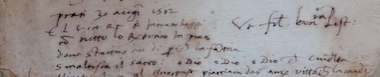

In a postscript (see image) he added: ‘The viceroy [Ramón de Cardona] appeared today with all of the army in Prato where they will be for two days because the infantry digests its sack. Oh God! Oh God! Oh God what cruelty!’[13]

Bibliography

Primary

Manuscript

Modena, Archivio di Stato, Archivio segreto Estense, cancelleria, ambasciatori, agenti e corrispondenti all’estero, Firenze, busta 11,

Printed

Anonymous. ‘Lamento e rotta di Prato.’ In Il sacco di Prato e il ritorno de’ Medici in Firenze nel MDXII. Pt. 1. Narrazioni in verso e in prosa. Bologna: Gaetano Romagnoli, 1880. Facsimile edition published in Scelta di curiosità letterarie inedite o rare dal secolo XIII al XIX. In appendice alla Collezione di Opere Inedite o rare. Dispense CLXXVII-CLXXVIII, 3-33. Bologna: Commissione per I testi di lingua, 1968

Anonymous. ‘La presa et lamento di Roma et le gran crudeltade fatte drento: con el credo che ha fatto li Romani: con un sonetto: et un successo di Pasquino’. In Antonio Medin and Ludovico Frati (eds.), Lamenti storici dei secoli XIV, XV e XVI, vol. 3, ch. 21. Facsimile reproduction. Bologna: Commissione per i testi di lingua, 1969

‘Documenti per la massima parte inediti che concernono il sacco di Prato e il ritorno de’ Medici in Firenze.’ In Il sacco di Prato e il ritorno de’ Medici in Firenze nel MDXII. Pt. 2. Documenti per la massima parte inediti. Bologna: Gaetano Romagnoli, 1880. Facsimile edition published in Scelta di curiosità letterarie inedite o rare dal secolo XIII al XIX. In appendice alla Collezione di Opere Inedite o rare. Dispense CLXXVII-CLXXVIII. Bologna: Commissione per I testi di lingua, 1968

Terrateig, Baron de. Politica en Italia del Rey Catolico, 1507-1516: correspondencia inedita con el embajador Vich. 2 vols. Madrid, 1963

Guyon, Fery de. Mémoires. Ed. A.L.-P. Robaulx de Soumoy. Brussels: Société de l’Histoire de Belgique, 1858

Secondary

Cohn, Henry J. ‘Götz von Berlichingen and the Art of Military Autobiography.’ In J. R. Mulryne and Margaret Shewring (eds), War, Literature and the Arts in Sixteenth-Century Europe, 22-40. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1989

LaCapra, Dominick. Writing History, Writing Trauma. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001

[1] ‘Documenti’.

[2] For a modern view see LaCapra, Writing History.

[3] ‘Et altre lacrimando desolate / Piangeran le innocente creature, / Che da l’altre fenestre eran gittate. / Tacian ormai le croniche e pitture, / Taccia le crudeltade preterite, / Ché queste son assai più delle altre oscure …’. Anon., ‘La presa et lamento di Roma et le gran crudeltade fatte drento: con el credo che ha fatto li Romani: con un sonetto: et un successo di Pasquino’, in Medin and Frati, Lamenti storici, vol. 3, ch. 21, 364.

[4] ‘Fessi in venti tre ore un tale assalto, / Che sprimer no lo può lingua mortale.’ Anon., ‘Lamento e rotta’, 10 (quotation), 18.

[5] Guyon, Mémoires, 23-31.

[6] Cohn, ‘Götz’, 28-9, 35 (quoting Schertlin).

[7] Ibid., 26-8.

[8] Modena, Archivio di Stato, Archivio segreto Estense, cancelleria, ambasciatori, agenti e corrispondenti all’estero, Firenze, busta 11, unnumbered fasc., letter dated 2 November 1494.

[9] ‘la victoria con mucha sangre y perdicion de gente francessa … Que ciertamente monseñor de Fox con el exercito frances ha ganado mucha reputacion’. Terrateig, Politica, 2: 182.

[10] Orators to the Ten, Prato, 30 August 1512, in ‘Documenti’, 134.

[11] Modena, Archivio di Stato, Archivio segreto Estense, cancelleria, ambasciatori, agenti e corrispondenti all’estero, Firenze, busta 11, fasc. 32, letters dated 26, 28 and 29 August 1512.

[12] ‘[Ben]che sia superstitione a poner fantasia alli augurii: pur non stato de advisar la Magnifica Vostra che tutta questa mattina hanno volteggiar alcuni corvi gracchiando intorno al sopra Prato: cosa che è stato notata da molti.’ Modena, Archivio di Stato, Archivio segreto Estense, cancelleria, ambasciatori, agenti e corrispondenti all’estero, Firenze, busta 11, unnumbered fasc., letter dated 29 August 1512. See also ‘Documenti’, 120.

[13] ‘[P]er mia parte vadvisasse de la presa di prato che se conquisto heri per forza di battaglia, e fecerono dentro questi spagnoli una strage e becheria la piu crudele che io vedesse mai, che tutte le strade, case, e le chiesie istesse erano piene di morti, e tutte le donne se sentivano li piu miserandi lamenti e piati che se possa dir. Et è posta a sacco tutta la terra. Io staro otto giorni che non saro di bon stomacho ne di bono animo per quello che ho visto et a[u]dito, e vorrei volontieri non ci esser stato. Prego che mandiare le qui [one word illegible] per le poste a nui vanno. Cercondassvi duno vaseletto di nebbiano sobietto, e uno vasello poi de scordo per me … El Vice Re è petrato hoggi con tutto lo exercito in prato dove staremo dui di perche la fanteria smaltisca il sacco. O Dio, O Dio, O Dio che crudeltà.’ Modena, Archivio di Stato, Archivio segreto Estense, cancelleria, ambasciatori, agenti e corrispondenti all’estero, Firenze, busta 11, unnumbered fasc., letter dated 30 August 1512. See also ‘Documenti’, 135-6.